Should Younger Investors Avoid Bonds Entirely?

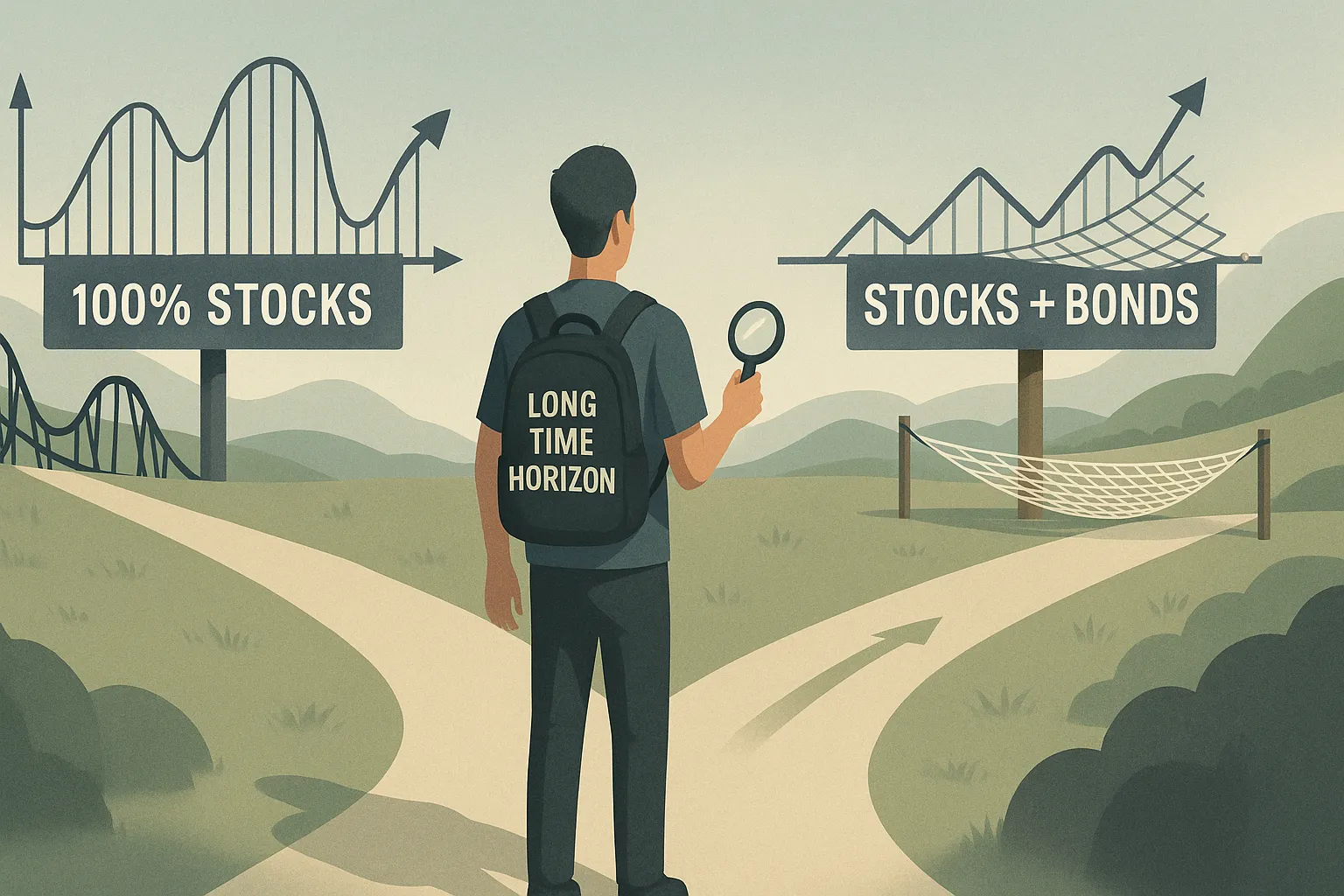

From 1987 through 2023, a portfolio made up entirely of U.S. equities (Vanguard Total Stock Market Index) returned 10.62% annually, while a blended 60/40 equity-bond portfolio returned 8.74%, according to historical data. That performance gap leads many to believe young investors—with decades until retirement—should stick to stocks alone. But is bypassing bonds completely a wise move?

It’s common to assume that bonds are only relevant for retirees who need steady income. Under that view, fixed income seems unnecessary for anyone under 40. This article explores why that’s an oversimplification—and what risks may come with skipping bonds altogether.

Key Takeaways

- Long investment horizons support stock-heavy allocations, but also expose investors to deeper short-term losses.

- Bonds reduce volatility, which may help prevent emotional decisions during major market declines.

- Skipping bonds can raise long-term returns, but comes with sharper fluctuations in value.

- Even small bond allocations can support better decision-making and liquidity for younger investors.

Why Many Young Investors Favor Stocks

It’s easy to see why stocks dominate the conversation for long-term investors. Over almost any multi-decade window, equities have outperformed bonds by a wide margin. When someone’s retirement is 30 years away, even small boosts in annual returns can translate into substantial wealth.

- Since 1926, U.S. large-cap stocks have averaged a 9.81% annual return.

- Long-term government bonds, by contrast, returned 5.42% annually over the same period.

That difference compounds quickly. For example, contributing $10,000 annually for 30 years at 10% would grow to more than $1.8 million. At 5%, the result is just under $700,000. With that kind of disparity, it’s understandable why bonds may seem like dead weight.

But this math only works if the investor stays committed through every downturn. That’s where theory and behavior can part ways.

Bonds as a Behavioral Anchor—Not Just a Yield Tool

Fixed income isn’t just about returns or income. It also provides psychological stability. In periods of market stress, bonds have often acted as a counterbalance—helping reduce the likelihood of panic selling.

- Hypothetical Example: Picture a 28-year-old investor who shifts their entire savings into equities right before a 40% drawdown. If that investor sells out near the bottom, the long-term return advantage of an all-stock portfolio disappears.

Bonds can reduce the chances of that scenario by:

- Smoothing portfolio volatility

- Offering short-term liquidity without selling stocks at depressed prices

- Providing a psychological cushion against fear-based decisions

Behavioral research consistently shows that investors tend to overreact during sharp losses. Reducing volatility—even at the cost of slightly lower returns—can help maintain long-term discipline.

What 2022 Taught Us: Correlations Can Shift

One reason bonds have been valued historically is their tendency to zig when stocks zag. But that didn’t hold in 2022. During the Fed’s tightening cycle, both asset classes declined—a rare instance of dual losses.

- The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index dropped 13% in 2022—its worst calendar year since tracking began in 1976.

- Equities fell simultaneously, as rising rates and recession fears rattled markets.

That experience prompted some investors to question whether bonds still serve a purpose. But the reality is: correlation isn’t fixed. In inflationary environments, both stocks and bonds may decline together. However, over the long run, these episodes are relatively rare—and bonds have generally helped during downturns.

For young investors with higher tolerance for volatility, this risk may feel acceptable. But it doesn’t mean the bond role is obsolete.

When Bonds Might Still Belong in a Young Portfolio

Avoiding bonds entirely isn’t the only option. Even a 5–15% allocation can serve a purpose—without meaningfully holding back equity-driven growth. Situations where bonds may be useful include:

- Short-term goals: Saving for a down payment within five years? Bonds can reduce volatility.

- Nervous temperament: A small allocation may help someone stay invested through turbulence.

- Rebalancing flexibility: Bonds can serve as “dry powder” to buy equities during dips.

What matters most isn’t the theoretical upside—but whether the investor can stick with the strategy through market cycles. If a small bond stake keeps someone from abandoning their plan, it can add real value—despite lowering returns on paper.

Behavioral Insight

Risk tolerance often feels higher in theory than it does during real losses. Younger investors can benefit from asking not just what’s optimal—but what’s practical for their own mindset.

All-equity portfolios can work—but only if the investor has already demonstrated they can weather deep drawdowns without panic. Otherwise, a small bond allocation may offer more than just lower volatility. It might be the difference between staying the course and locking in losses.